Background

“Co-first” is when two or more individuals are noted as providing the same or equal first-author-level contribution to a published work. Such co-first authorships are becoming more common, particularly in the biomedical fields, where projects are becoming more and more ambitious, requiring more and more diverse skill sets as well as intense multi-year collaborative efforts to come to fruition. As a computational biologist, I have had the priviledge of working with many excellent bench biologists. By combining my computational skills with their experimental bench skills, we have been able to pursue and address much more interesting biological questions in health and disease. So when we finally publish our collaborative works, we share co-first authorship under the mutual understanding that we have both provided equal first-author-level contribution to the published work.

Problem

While my colleagues and I recognize the value of each other’s contributions, publications still require one individual to be physically listed first. And unfortunately, publishers have been rather slow in properly recognizing such co-first authorships with readily visible annotations, particularly online.

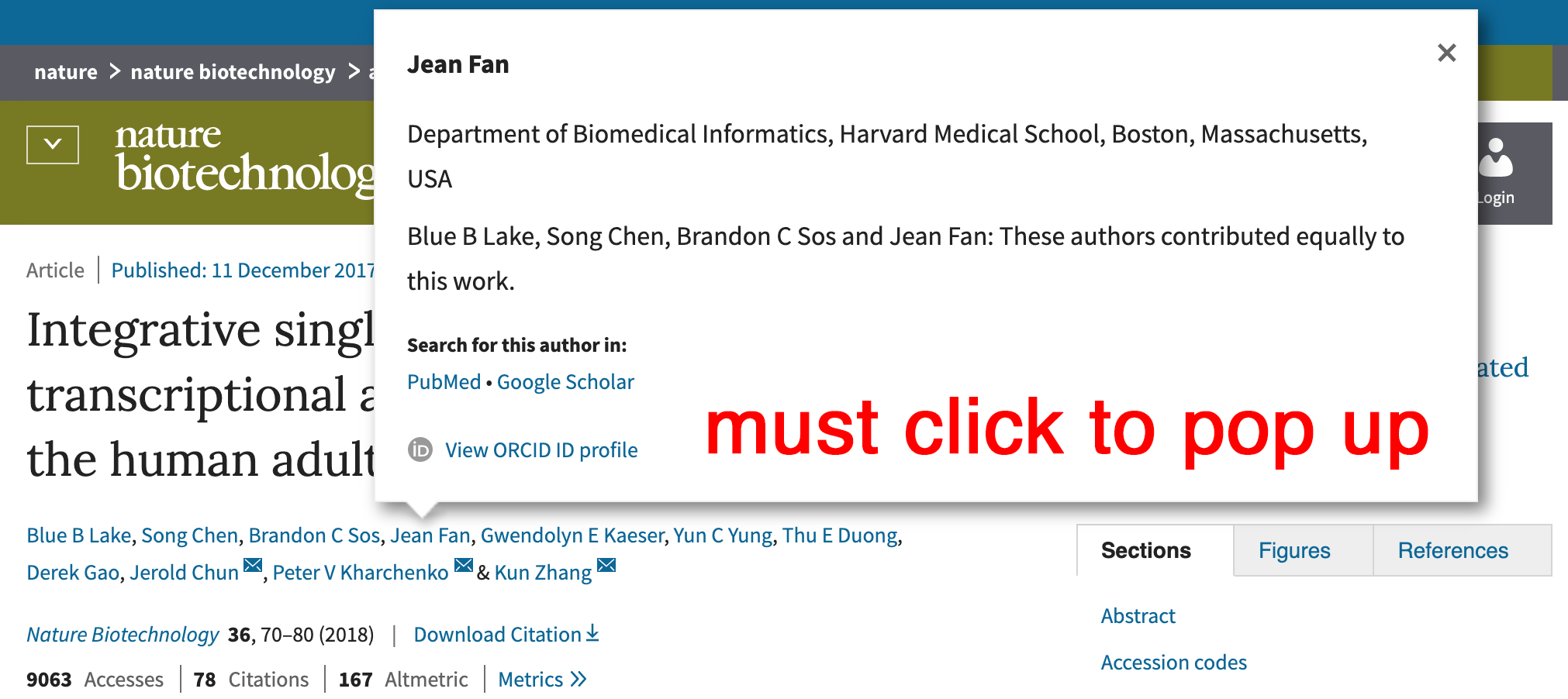

For example, in our 2018 Nature Biotechnology paper, unless the reader clicks on each co-first author’s name, the fact that multiple people contributed equally to this work is not evident:

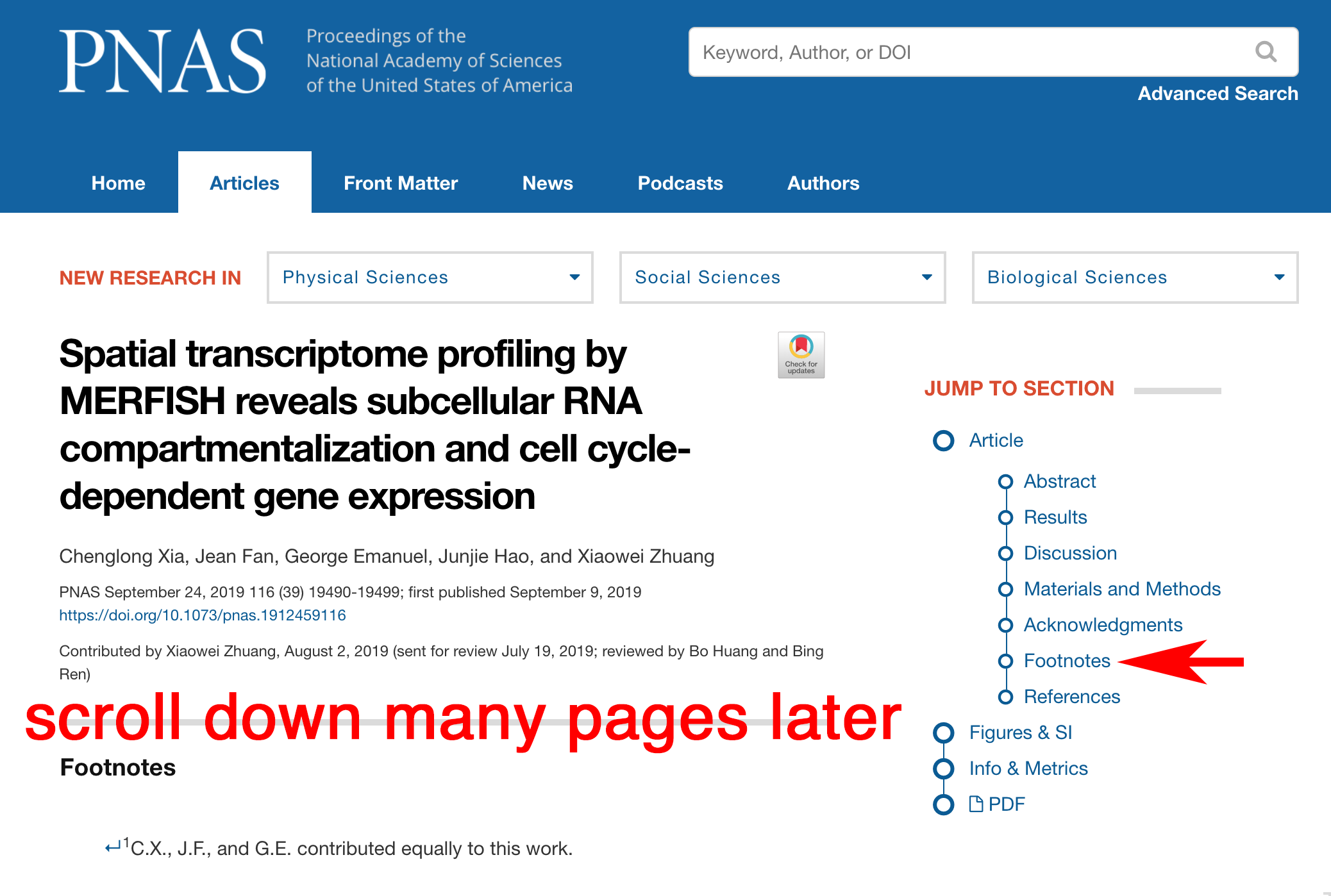

This problem is not journal specific or limited to older articles, as in our very recent 2019 PNAS paper, unless the reader scrolls all the way to the end of the paper’s footnotes, the fact that multiple people contributed equally to this work is not evident:

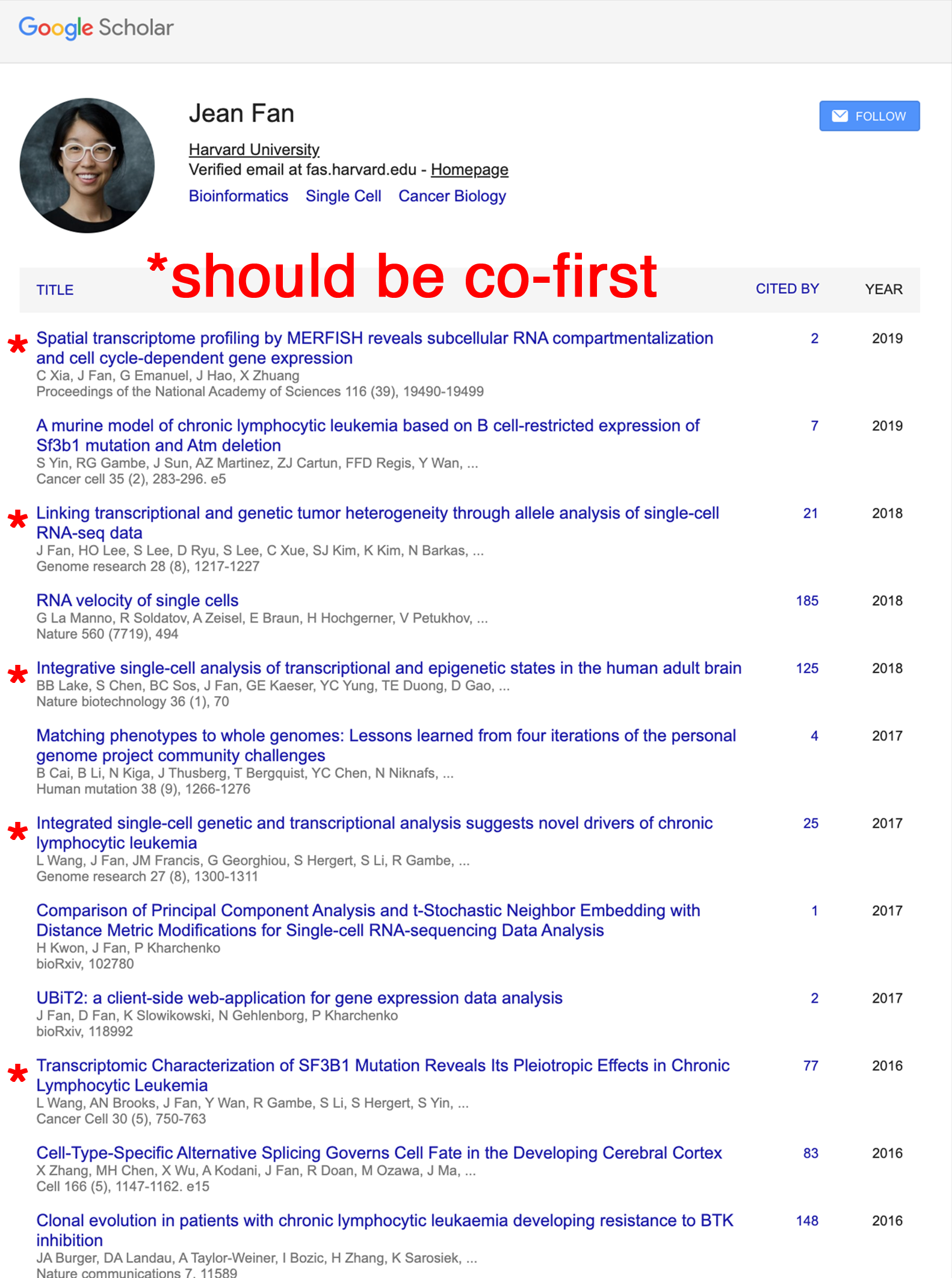

Of course, some journals including Genome Research, PLOS, and others are better at recognizing co-first authors than others, but only on their own websites. Such co-first author information does not appear to be passed on to reference tools or databases such as Google Scholar or NCBI’s My Bibliography, where indications of co-first authorships are no where to be seen:

Why this matters (why you should care)

To the co-first authors: Metrics such as the number of first author papers still play a substantial role in hiring, tenure, grants, and many other career advancement opportunities and decisions. Therefore, the ability for a reviewer to quickly recognize your co-first author publications and distinguish these publications from middle author ones may very well influence their decisions.

To the last authors: Without proper recognition of equal contribution by co-first authors through proper annotation on publishing websites, these large-scale multi-year collaborative projects will become more difficult to pitch to candidate co-first authors. You will be effectively asking students to put in the effort of a first author but ultimately receive the recognition of a second author.

To the editors: Identifying leaders in the various scientific fields to recruit as reviewers is already challenging enough. The inability to quickly recognize co-first authorships in publications is likely limiting your access to a pool of qualified candidate reviewers, who may be co-first but just listed second.

To the scientific field: Unfortunately, multiple studies have suggested that author order is not equitable with regards to sex for authors claiming equal contributions. Thus, if women or other minorities are more likely to be listed second in equal contribution co-first authorship situations, the failure to properly recognize co-first authorships may have widespread consequences as related to the aforementioned points regarding co-first authors, last authors, and editors and thus greatly limit the advancement of women and other minority voices in science.

Personal story

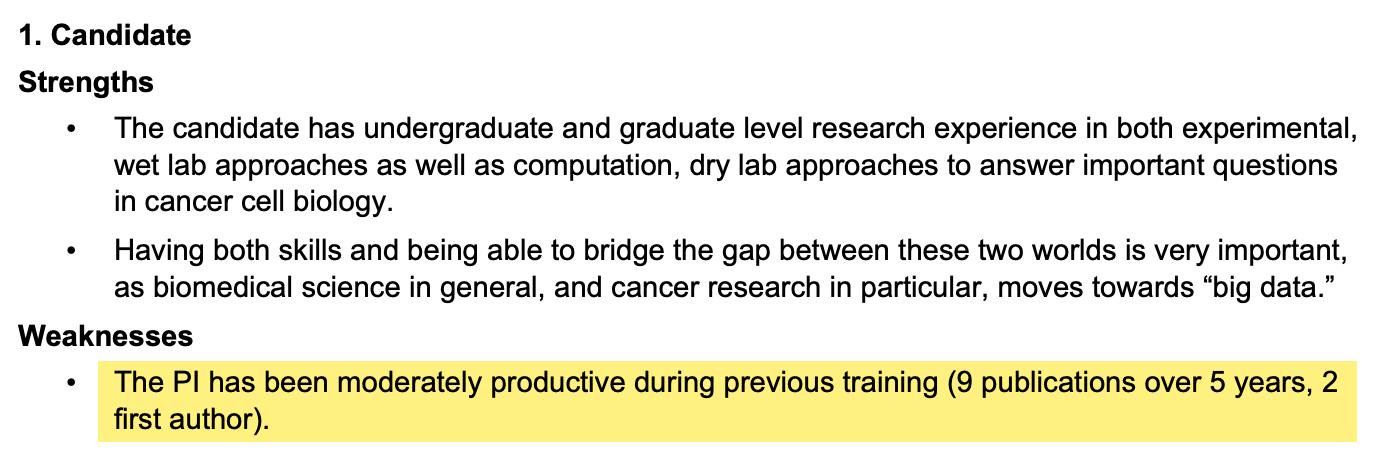

As winner of the 2019 Nature Research Award for Inspiring Science, I had the opportunity to speak with a number of editors and staff at Nature Research, in particular regarding the challenges I have face as a woman in science. One particular “fail tale” that I shared was about recent grant, where a reviewer noted my weaknesses as a candidate to be the following:

During my previous training period, I have published 9 publications, 2 of which were first or co-first where my name was listed first. But an additional 3 were co-first where my name was not listed first. The reviewer likely did not have time to click on each publication and correctly identify which were co-first or just referenced my NCBI My Blibiography, which did not indicate such co-first authorship information. Having been in the same boat before with a limited amount of time to look through a large number of candidate profiles and applications, I really can’t fault the reviewer for their oversight.

Solution

If we insist as a scientific community to rely on such arbitrary metrics of productivity, we should at least make it easier to accurately use them. Here is even a mockup:

What we can do in the meantime

While we can pressure decision makers and publishers towards making the proper modifications, there are also things we can do as academics to better ensure that co-first authorships are properly recognized.

For one, students/mentees/trainees can clearly and explicitly state on their CVs, biosketches, grant/faculty/fellowship applications, etc how many first and equal-contribution co-first author papers they have produced. Likewise, advisors/mentors can clearly and explicitly state in letters of recommendation how many first and equal-contribution co-first author papers students have produced. Do not rely on reviewers to be able to count accurately.

Publications noted on lab websites can also be modified to more clearly recognize equal contribution by co-first authors.

Until equal-contribution co-first authors are recognized as truly being equal, such as with readily visible annotations on publication websites, all co-first authors will be equal but some will be more equal than others.